History of Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital

THE EARLY YEARS

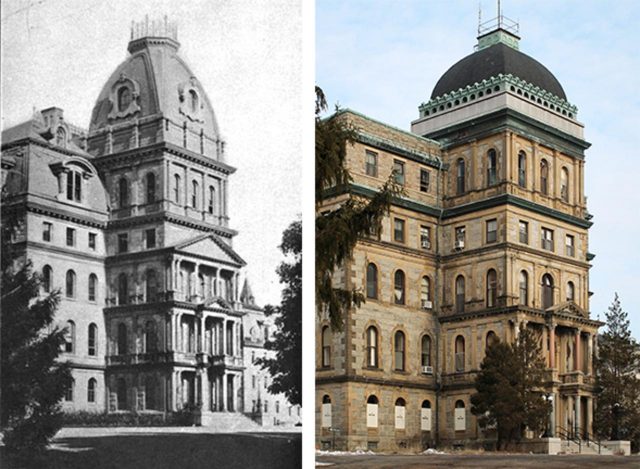

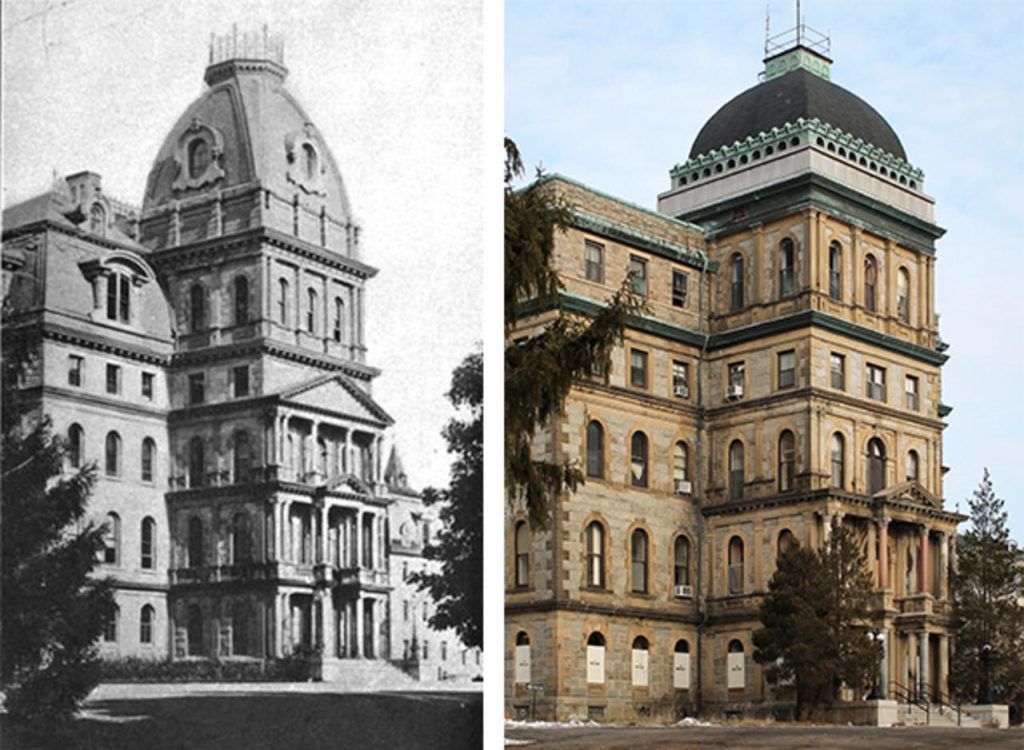

New Jersey’s only state asylum was overcrowded. The Lunatic Asylum, located in Trenton, only had room for no more than five hundred patients, but at present the hospital housed more than seven hundred. Relief was necessary. After visiting approximately 42 different locations, officials approved purchase of a portion of a few farms and lots, on August 29th 1871 near Morristown and a short distance from the Morris and Essex Railroad. The plots of land contained fertile soil, rock quarries for mining stone, a sand pit for building materials and reservoirs for water and ice access. The new asylum, when completed, would hold approximately 600 patients, with the large main building to be completed in sections as usage detailed.

The plan of the main building was drafted to allow for a total of 40 wards split into 2 wings, one wing for each sex. There was to be no communication between wards. The corridors also served another purpose other than just separating wards: they provided for fire protection, so that a fire would be unable to spread past a single section of the building.

Upper floors in the center section contained apartments for employees, and the third story contained the amusement room and chapel for patients. Samuel Sloan was named architect of the main building and its smaller supporting buildings. Sloan chose to follow the Kirkbride Plan, a list of ideals pertaining to hospital design created by Thomas Story Kirkbride. There would be a center section for administrative purposes, then a wing on each side with 3 wards on a floor. Each ward would be set back from the previous one so as to allow patients to take in the beautiful grounds from their ward. Each ward was designed to accommodate 20 patients, with a dining room, exercise room and activity room. The wards were furnished with the highest quality materials such as wool rugs, pianos and fresh flowers.

The State Lunatic Asylum at Morris Plains opened its doors to receive its first 342 patients in 1877.

Though the institution was complete and operational, the grounds surrounding the area were still in a state of transition, and officers often noted the fact that they may be more successful in treatment with completed grading of the grounds. It was believed that a nice aesthetic environment was a great factor in the recovery process.

Patients worked on the farms growing and raising food, and performed hard labor tasks in the clearing away of building debris, excavating for roads, and sodding grounds. The plan of the institution called for carriage drives ending at all doorways, and a central road leading up to the front entrance flanked by trees on both sides. Grounds on both sides of the wings would provide for simultaneous exercise of both sexes while keeping them separate.

By 1895 the State Lunatic Asylum is operating at 325 patients over capacity. The overcrowding is a major health and cleanliness issue, resulting in a small outbreak of typhoid fever, eventually blamed on the water supply. The passing of years brought no relief for a bursting hospital. 1,189 patients bedded down in an institution meant to hold only 800 every night. Cots were placed in activity rooms, exercise halls and hallways in order to try and find sleeping arrangements for all. “From a sanitary point of view these cots are an abomination,” declared the board of managers. Cots were set up and taken down on a daily basis on the hallways, and were not able to be cleaned between uses. Patients often soiled themselves during the night, and the cots were simply handed out again the following evening.

The Asylum scrambled to create more housing. By 1901 the new dormitory building was completed and quickly filled, thereby slightly easing crowding issues. Patients were once again able to be grouped according to disease classification and had access to exercise and activity rooms again. The new dormitory building would gain infirmaries and operating rooms in the coming years, as well as a bowling alley which was extremely popular among patients and staff during the winter months when outdoor exercise was not an option. By 1903 the hospital had crossed over the 1,500 patient mark, continuing its steady climb. Once again the numbers were an issue.

A state-of-the-art electrotherapeutic room is installed in the main building, and the women’s wing of the dormitory receives a hydrotherapy room. Medical Director Britton D. Evans writes of this new treatment in his report in 1906, “It is well recognized that the application of water at varying degrees of temperature and pressure exerts influences of a valuable therapeutic character upon the entire human economy and aids the recuperative powers of the body.” Female patients are now able to receive treatment for their afflictions through use of douches, massages, and hot air cabinets. A hydrotherapeutic treatment room for male patients is opened the following year.

By 1911 the State Asylum at Morris Plains held 2,672 patients, and cots are once again placed in corridors and activity rooms. A photographic department is established and begins documenting patients in hopes of cataloging facial expressions and characteristics which go with certain mental disorders. A dental clinic opens for treatment of teeth ailments. A Tuberculosis pavilion is finished and occupied the following year, as well as a new larger fire department house, and enlargements to the greenhouse and piggery.

An Industrial Building opens in 1914, allowing for more jobs for patients than just manual labor jobs in farming or groundswork. It is a widely popular belief during this time that putting the insane to work in certain circumstances is beneficial both to the patient and the institution. Those who are chronically ill, restless in the day and night are thought to be aided in their general well-being by working out some of the over supply of blood to the brain. Within the walls of the new building, male patients are able to make brooms, rugs, brushes, carpets, and do printing and bookmaking.

1915-1949

In 1916 Women begin participating in sewing and arts and crafts on the top floor of the Industrial Building, and a small patient library is founded with 184 volumes of books. Annexes to the Dormitory building open in 1917 to provide more space for housing. During World War I, the hospital faces major staffing shortages with male employees due to the draft. Medical Superintendent Britton Duroc Evans passes away in 1920 while still serving the position, and Marcus A. Curry is named his successor.

The next few years saw much progress in the department of building construction. The Voorhees Cottage and Knight Cottage are opened as homes for nurses, as well as cottages for senior physicians and the superintendent. The Psychiatric Clinic Reception Building opens its doors in 1923 and all operating rooms, laboratories and x-ray equipment are moved to the new building. A Social Service Department is instituted, in charge of letting patients out for “trial” visits to help them assimilate back into the real world. Parts of the hospital are set aside of “War Risk Patients”- veterans from World War I suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The hospital was blessed with its modern-day name, Greystone Park Psychiatric Center, in 1924. The new reception building, dubbed the Curry Building after Medical Superintendent Marcus Curry, opened in 1927, as well as a slew of other buildings- a new fire station, power plant, greenhouse, and auxiliary buildings. The Men’s Occupational Therapy Building opened that same year, allowing for patients to take on new duties in service to the hospital such as tailoring and woodworking. A Women’s Occupational Therapy Building would follow a few years later.

1929 and 1930 proved to very trying times for Greystone. In the two year span, three fires severely handicapped the institution’s ability to treat the mentally ill. The most devastating of the three fires, on November 26, 1930, was ruled to have originated from faulty electrical wiring on the sixth floor of the center section. Some patients were tied to trees with fireman’s ropes to prevent escape after evacuation. The fourth floor north wards were destroyed as well as the central tower. Once rebuilt, the fourth floor in the north wards never matched the rest of the hospital in construction and style again.

The new Chest Building opened to act as a TB Treatment Center and 30 Ellis Drive opens, with a senile building under construction. This trio of buildings would make up the Ellis complex. The state of New Jersey opens the Marlboro State Psychiatric Hospital in Holmdel in 1931, and patients are transferred over the next few years down to the new hospital to help with overcrowding issues. However Greystone officials are faced with a new problem: patients transferred to Marlboro must pass a series of tests, and often the most able-bodied patients are removed from the campus, leaving older or more seriously ill patients behind. A change in the population begins, and there is a shortage of patients capable of work or occupational therapy. Some of this need was filled by working men brought in by the state through the WPA program and other similar programs starting around 1935.

4,886 patients called Greystone Park home in 1935. Over the next few years a handful of buildings for patient and staff housing opened. By 1940 shock and endocrine therapy had taken over as the main treatment methods for mental illness at Greystone. New wings attached to the Dormitory Building and Units A and B were completed that same year.

In 1947 a major study was conducted involving Greystone and Columbia University in New York. Dubbed the “Columbia-Greystone Project,” It forever changed the world of psychosurgery by concluding that lobotomies were not an effective treatment option for mental disorder.

1950-PRESENT

Patient population numbers would peak in 1953 with 7,674 residents. This spike in population was partially because of returning veterans from World War II suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Greystone’s most famous patient, folk singer Woody Guthrie, was committed to Greystone due to his battle with Huntington’s Disease in 1956. He stayed in “Wardy Fourty” as he referred to it, also known as Ward 40 in the main building. Pete Seeger and a young Bob Dylan were among some of his more well-known visitors during his stay at “Gravestone.” He was eventually transferred to a New York hospital in 1961, and died there six years later.

The glory days long gone, the 1970s and 1980s saw a movement in mental health towards deinstitutionalization. Suddenly states around the country preached that mental health patients were better off living in the home with their families and being treated by the community than staying in removed surroundings in a hospital for a long-term stay. Two factors caused this sudden change. New psychological drugs were able to control patients much more effectively than previous methods ever could, and suddenly dangerous patients were capable of existing in the community in a less harmful state. Secondly, laws were passed in the 1970s forbidding patients to work unless paid fairly, which meant at least minimum wage. Suddenly hospital costs skyrocketed, as patients were no longer able to work in order to defray fees.

10 and 50 Ellis were renovated and reopened in 1974 as patient housing and a brand new hospital deemed the Central Avenue Complex opened in 1975, replacing the Medical Clinic Building. The Curry building closed soon after, as well as the Chest Building due to rapid decrease in tuberculosis.

Due to the landmark Doe vs. Klein case in 1974, Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital was forced to build community homes for patients to provide halfway house type living situations, and adequate staffing and patient care was required of the institution. Twenty “independent living” cottages opened in 1982.

By 1988 all patients had been moved out of living in the main Kirkbride building, and the wings were basically abandoned. Now only the center section was used for administrative purposes. The dormitory closed a few years later in 1992.

Students of Drew University led an effort to try and get Greystone Park Psychiatric Center listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but were turned down. The Register claimed that the study submitted focused too much on the Kirkbride building, and that they wanted to see the entire hospital system submitted as a National Historic District. However, one student did manage to get the gas house placed on the Register.

Greystone had dark years in the 1990s. Patient escapes became commonplace, including criminals and sex offenders. Staff were accused of abuse and rape, and some female residents ended up getting pregnant. Buildings were falling apart and lacking in basic creature comforts. Greystone was in danger of losing its accreditation from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. If this were to happen, the hospital would lose out on approximately $35 million dollars annually from Medicaid and Medicare. This was obviously not an option. A Senate task force was appointed to conduct a 6-month probe on how to improve conditions, and the hospital was able to pass.

In 1997 the original tuberculosis pavilion was demolished, along with the morgue, a large garage, the print and tailor shops, and several employee dormitories and cottages. A new era for Greystone had begun, and the state was realizing it did not include many of its decaying antiquated buildings.

Suddenly attention was on the Kirkbride building. The State of New Jersey released a report in 1999 stating the behemoth was “not suitable for long-term future use.” The report went on to say that a new smaller building should be built and the hospital consolidated under this structure, and that while older structures should be razed, the main building should be saved due to historical significance.

Governor Christine Todd Whitman ordered the now 550-bed facility closed within the next three years in 2000.

Morris County purchased approximately 300 acres of the Greystone Park Psychiatric Center property in 2001 for one dollar, with the stipulation that it would clean up asbestos and other environmental hazards on the site within its decaying buildings. When this land was sold, a law was also passed that Greystone land cannot be used for any purpose other than “recreation and conservation, historic preservation or farmland preservation.” This meant no commercial development and no condos or townhomes.

The major effort to clean up the larger decaying buildings which still stood, and were viewed as eyesores, began in 2005 with the demolition of the dormitory. Ground was broken on the new hospital building, located up the hill across the street from the Ellis complex. The entire Curry Complex, including the Medical Clinic Building, the Curry Reception Building and the Employee Cafeteria came down in 2007 and 2008. The trio of buildings known as the Ellis Complex were cleared to make way for a parking lot.

On July 16, 2008, after countless unexplained delays, patients were finally moved into the new hospital building. Administration and other departments followed in suit. Today almost all hospital services have relocated to the brand new complex. Morris County has installed skating rinks and a ball field on its 300 acre share, and plans to incorporate a dog park where the Curry Complex once stood, as well as an athletic complex for disabled athletes. The Central Avenue Complex is planned to become a mall for nonprofit charitable agencies.

Currently the state of New Jersey is looking at options for what to do with the rest of the surplus Greystone land and buildings. A group called Preserve Greystone has formed and hopes to work with the state and government to preserve both open space and the remaining buildings from the hospital. Currently the future is unknown, and the buildings, including the large Kirkbride building, sit exposed to the elements, slowly decaying and following the footsteps of other Greystone buildings, only to eventually meet the wrecking ball after too much damage has been incurred.